The Acceptance-Based Anxiety Reduction Method: ACT Therapy Principles

Anxiety reduction based on principles of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

Anxiety reduction based on principles of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

For months, Sarah, a 32-year-old marketing manager, felt like she was at war with herself. Every work presentation triggered a cascade of internal warnings: "You're going to mess this up," "They'll realize you're not qualified," "Just cancel and avoid the embarrassment." She spent hours trying to suppress these thoughts, debating with them, analyzing their validity—only to find they grew louder and more insistent. She began avoiding meetings, declining opportunities, and her world gradually shrank as she devoted increasing energy to controlling what felt like a dangerous and unpredictable mind. This exhausting battle, fought in the silent theater of her own consciousness, left her drained, disconnected from her professional ambitions, and feeling fundamentally broken.

Sarah's experience represents a universal human struggle against our own internal experiences. We've been culturally conditioned to believe that psychological health means controlling, eliminating, or fixing "negative" thoughts and emotions. The anxiety itself becomes the enemy, and we wage a daily war against it using strategies that feel intuitively right: suppression, avoidance, distraction, and rigorous self-criticism when these methods inevitably fail. Yet what if this entire framework is flawed? What if the path to psychological freedom isn't through winning this war, but through laying down our weapons?

This article explores Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a revolutionary psychological approach that proposes a radical alternative to the control-and-eliminate model of mental health. Pronounced as the word "act," ACT is not about passive resignation but about active, mindful engagement with life, even when anxiety is present. Developed by psychologist Steven C. Hayes in the late 1980s, ACT belongs to the "third wave" of behavioral therapies and is grounded in a scientific theory of human language and cognition called Relational Frame Theory (RFT).

The core insight of ACT is both simple and profound: much of human suffering stems not from pain itself, but from our struggle against it. The rigid attempts to control or avoid uncomfortable thoughts and feelings—a process known as experiential avoidance—often create more problems than they solve. ACT shifts the therapeutic focus from symptom reduction to valued living. Instead of asking "How do I get rid of anxiety?" it encourages us to ask: "What would I do with my life if anxiety were no longer an obstacle?" and then provides the psychological skills to move in that direction, anxiety and all.

Through its six core processes, ACT fosters psychological flexibility—the ability to be fully present, open up to our experiences, and take action guided by our deepest values. This is the antithesis of rigidity and avoidance. Research, including meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials, shows ACT is effective for a wide range of issues, from anxiety and depression to chronic pain and workplace stress. A 2022 systematic review specifically found it to be an efficacious, non-pharmacological alternative for reducing anxiety in older adults, a group often underrepresented in treatment studies.

As we delve into the principles and practices of ACT, we will explore not just a therapy model, but a fundamentally different way of relating to our own minds. This is a journey from a life dominated by the fear of internal experiences to a life directed by purpose and meaning. It’s about learning to make room for anxiety without letting it drive the car. For individuals like Sarah, and for anyone feeling trapped in a cycle of worry and avoidance, ACT offers a path forward—not to a pain-free life, but to a vital, engaged, and values-driven life, with all its rich and challenging human textures.

We live in an age of unprecedented anxiety. While global connectivity, technological advancement, and material comfort have reached heights our ancestors could scarcely imagine, so too have levels of stress, worry, and psychological distress. The World Health Organization has labeled stress the "health epidemic of the 21st century," and data consistently shows rising rates of anxiety disorders across diverse populations. This paradox of progress suggests that our modern environment, for all its benefits, may be uniquely suited to trigger and exacerbate the very cognitive processes that lead to suffering.

At the heart of this epidemic is a critical mismatch. Our brains, evolved for survival on the savanna, are now tasked with navigating a world of abstract symbols, endless choice, social comparison via curated digital personas, and constant, low-grade threat alerts from news cycles. The human capacity for language and symbolic thought, which allows us to plan, innovate, and build civilizations, has a shadow side. It enables us to suffer over events that have never happened, relive past pain as if it were occurring now, and treat our own self-evaluations—"I'm not good enough," "I'm a failure"—as literal, undeniable truths. This process is known in ACT as cognitive fusion, and it is a primary engine of anxiety.

Experiential avoidance, the natural counterpart to fusion, is our go-to strategy for managing the distress this creates. When we feel the pang of anxiety, the pull of a painful memory, or the weight of a critical thought, our instinct is to push it away. We might:

The cruel irony, as shown in research on conditions like Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), is that these strategies are negatively reinforced. In the very short term, avoiding a social event does relieve the anticipatory anxiety. Suppressing a thought can make it disappear for a few seconds. This temporary relief teaches our nervous system that avoidance works, cementing it as a habitual response. In the longer term, however, the cost is catastrophic. Avoidance shrinks our lives. It teaches us that we are fragile, that certain experiences are intolerable, and it often amplifies the very thoughts and feelings we're running from. The energy expended in this internal struggle is energy drained from living.

Traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), the long-standing gold standard for anxiety, has helped millions by teaching them to identify, challenge, and restructure "distorted" or "irrational" thoughts. The model is logical: change your thoughts, and you'll change your feelings. For many, this is profoundly effective. Yet, a significant portion of individuals find limited relief, or find that their anxious thoughts are surprisingly resistant to logical debate. When a thought like "I'm going to be abandoned" is rooted in deep-seated early experiences, simply arguing against it can feel invalidating and can turn into another round of exhausting mental combat.

This is the landscape into which ACT emerges. It does not see anxious thoughts as "distortions" to be corrected, but as natural products of a verbal, evaluative mind trying to protect us. The problem isn't the presence of the thought "I will fail," but our fusion with it—the belief that because we think it, it must be important, true, and a command we must obey or frantically disprove. ACT proposes a paradigm shift: We cannot always choose the thoughts and feelings that show up, but we can choose how we respond to them. The goal is not to have a "better" or "quieter" mind, but to develop a different relationship with the mind we have—one of mindful awareness, compassionate distance, and values-based action.

The failure of our old tools—rigid control and avoidance—isn't a personal failing; it's a design flaw in our approach. We've been trying to use the thinking, problem-solving part of our mind to solve the problem of having a thinking, problem-solving mind. ACT offers a way out of this loop by changing the game entirely. It equips us not with better weapons for our internal war, but with the skills to make peace and redirect our vitality toward what truly matters. If you're interested in how modern technology can complement this journey by providing objective data on your stress and recovery, you can explore our blog for more on integrating wellness tech with psychological practices.

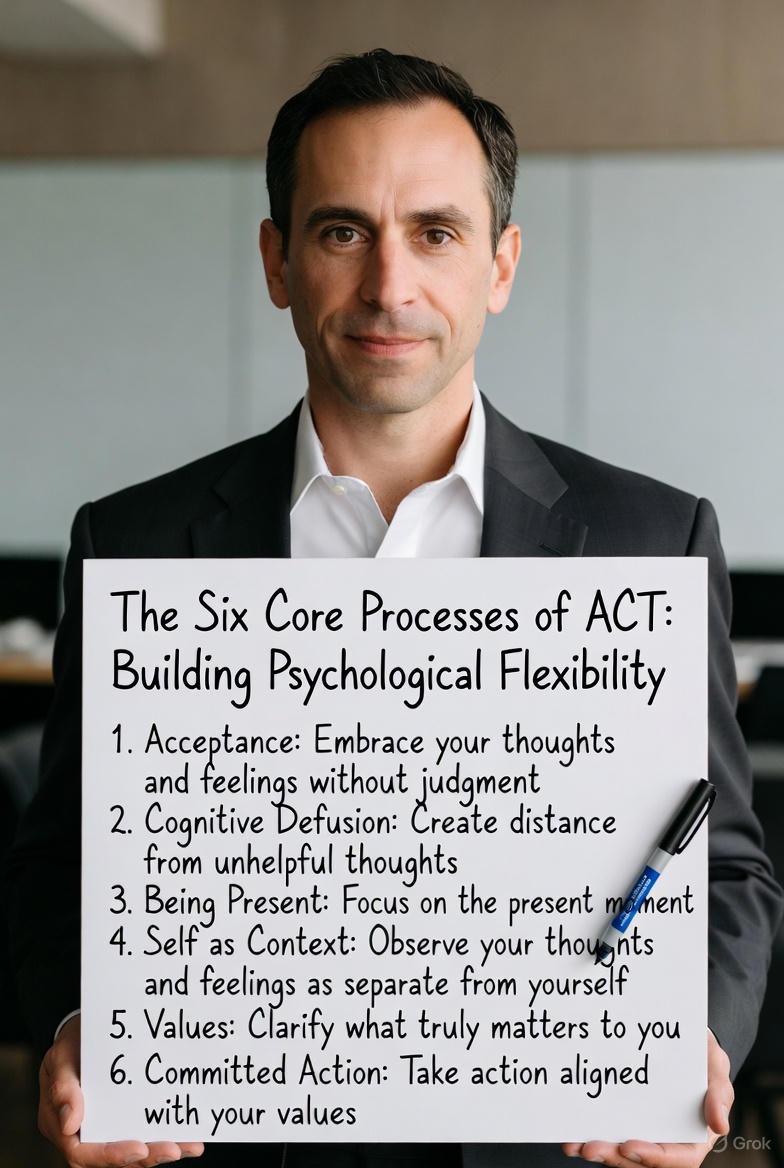

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is more than a set of techniques; it is a coherent philosophy of human suffering and vitality grounded in modern behavioral science. At its simplest, ACT can be defined as a mindfulness-based behavioral therapy that increases psychological flexibility through six core processes: Acceptance, Cognitive Defusion, Being Present, Self-as-Context, Values, and Committed Action. Its ultimate aim is not to eliminate difficult private experiences but to help individuals live fuller, more meaningful lives even in their presence.

ACT’s development in the late 1980s by Steven C. Hayes and colleagues marked a significant evolution from traditional behavior therapy. It emerged from Relational Frame Theory (RFT), a behavioral account of human language and cognition. RFT explains how we learn to relate ideas, symbols, and events arbitrarily. For instance, if we learn that "darkness" is related to "danger," we may then feel fear not just in actual dangerous dark places, but also when speaking about the "dark" times in our lives or having "dark" thoughts. Our minds become incredibly adept at creating networks of relations, allowing for creativity and communication, but also for getting entangled in verbal networks of threat, past, and future that generate immense suffering in the present moment.

This theoretical foundation is crucial because it explains why we get so hooked by our thoughts. In the ACT model, psychological inflexibility—the opposite of the therapy's goal—arises from the core pathologies of cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance. Fusion means we are "hooked" or "entangled" by our thoughts, seeing the world through them as if they were transparent reality rather than looking at them as transient bits of language. Avoidance is the driven behavior that results from fusion: we must avoid what our mind says is dangerous (e.g., anxiety, rejection, failure).

ACT’s six processes work together to dismantle this inflexible, suffering-producing system and build a new, flexible one:

These are not linear steps but interconnected facets of psychological flexibility. Mindfulness practices (present-moment awareness) fuel defusion and acceptance. Defusion creates space to choose values over avoidance. Values give purpose and direction to committed action. And taking committed action inevitably brings up internal barriers, which are met with acceptance and defusion, creating a virtuous, empowering cycle.

A key differentiator between ACT and traditional CBT lies in their approach to thoughts. While CBT often focuses on the content of thoughts (e.g., "Is it accurate that you will fail?"), ACT focuses on the function and context of thoughts (e.g., "Are you fused with this thought? Is believing it helping you move toward your values?"). ACT assumes that trying to control thoughts is often part of the problem, not the solution. Therefore, it teaches skills to change our relationship to thoughts, diminishing their unhelpful impact without engaging in a struggle for control.

Extensive research supports ACT's efficacy. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 39 randomized controlled trials found it to be significantly effective for anxiety, depression, addiction, and chronic pain. Studies have shown it to be as effective as traditional CBT for many conditions, and particularly beneficial for people for whom cognitive restructuring has not worked. Its transdiagnostic nature—targeting core processes like fusion and avoidance that underlie many disorders—makes it a versatile and powerful tool for enhancing general psychological well-being, not just treating pathology. To understand the philosophy behind creating tools for sustainable wellbeing, you can read about our vision and values on our story page.

Psychological flexibility is the cornerstone of mental health and vitality in the ACT model. It is defined as the ability to be fully present, open to our experiences, and to take action guided by our values. It is the opposite of being rigidly fused with thoughts or reflexively avoiding discomfort. This flexibility is built through the mindful cultivation of six interrelated processes. Think of them not as sequential steps, but as interlocking facets of a single, dynamic skill set for living well.

Acceptance in ACT is an active process, not passive resignation. It is the willing embrace of our present-moment internal experience—anxiety, sadness, memories, urges—without defense. It means dropping the struggle to make a feeling go away and instead, saying, "Okay, this is here. I can feel this and still do what matters."

Defusion means "de-fusing" or separating from our thoughts. It involves creating psychological distance so we can see a thought as a mere string of words or a passing image in the mind, not as a literal truth that demands our obedience. When fused, the thought "I'm worthless" feels like a devastating fact. When defused, it is seen as "I'm having the thought that I'm worthless."

This process is about flexible, fluid contact with the present moment. It is the opposite of being lost in ruminations about the past or worries about the future—states that are hallmarks of anxiety. Being present allows us to experience the world directly, richly, and to respond effectively to what is actually happening, not just to our mental projections.

This is perhaps the most subtle of the ACT processes. It involves connecting with the part of you that is the consistent, conscious perspective from which you observe all your experiences. It is not your thoughts, feelings, roles, or body (which are all content), but the context or space in which that content arises and changes. This is the "you" that was there when you were 5, 15, and 25—the noticing "you" that has witnessed all the changes in your life.

Values in ACT are verbally constructed, global, desired life directions. They are not goals (which can be achieved) but qualities of action you want to embody, like being curious, courageous, compassionate, or connected. They answer the question: "What do you want to stand for in life?"

This is the behavior-change wing of ACT. It means taking effective, values-guided action, repeatedly, even in the presence of obstacles. It involves setting specific, achievable goals that are stepping stones along your valued paths.

Together, these processes form a dynamic, self-reinforcing system for living. They move us from a life organized around avoiding internal demons to a life organized around pursuing external vitality. For more practical examples of how to integrate awareness and action into daily life, our FAQ section addresses common questions about building sustainable wellness habits.

The principles of ACT are not merely philosophical; they are supported by a robust and growing body of neuroscientific and clinical research. Understanding this science demystifies how acceptance—a concept that can seem counterintuitive—can lead to tangible reductions in suffering and greater wellbeing. At its core, ACT works by fundamentally rewiring maladaptive cognitive and emotional habits and disrupting the cycle of anxiety at multiple levels.

Modern neuroscience helps explain the processes ACT targets. When we experience cognitive fusion with an anxious thought ("This feeling is dangerous!"), it activates the brain's default mode network (DMN), associated with self-referential thinking, mind-wandering, and rumination. This state pulls us out of the present moment and into a narrative about ourselves that is often threatening. Simultaneously, the amygdala, the brain's threat detector, fires, triggering the fight-flight-freeze response. Experiential avoidance is the behavioral output of this activated threat system.

The problem is, each time we avoid and get short-term relief, we strengthen the neural pathway linking the anxious thought (via the DMN) to the threat response (amygdala) and the avoidance behavior. This creates a deeply ingrained, automatic habit loop. Traditional suppression efforts often backfire, leading to a rebound effect where the targeted thought or feeling returns with greater intensity (the famous "Don't think of a white bear" phenomenon).

ACT interventions are designed to interrupt this loop and build new, flexible neural pathways.

The theoretical model is borne out in clinical outcomes. A seminal 2008 randomized controlled trial on Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) provides strong evidence. The study tested an acceptance-based behavior therapy (ABBT) drawn from ACT and other mindfulness-based approaches. The results were striking: 78% of treated participants no longer met criteria for GAD at post-treatment, and 77% achieved high end-state functioning. These gains were maintained at 3- and 9-month follow-ups. Crucially, the treatment worked by the proposed mechanisms: it led to significant decreases in experiential avoidance and increases in mindfulness.

Furthermore, a 2022 systematic review focusing on older adults—a population with chronic, often treatment-resistant anxiety—concluded that ACT is an efficacious, non-pharmacological alternative. The review found consistent evidence that ACT reduces both anxious and depressive symptoms in this group, highlighting its utility across the lifespan.

ACT’s effects extend beyond symptom checklists. Research shows it enhances psychological well-being (PWB), which includes dimensions like environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relationships, and purpose in life. This is the ultimate goal: not just the absence of anxiety, but the presence of vitality. By changing our relationship with inner experiences, we free up psychological resources previously devoted to internal combat, allowing them to be invested in building a rich, meaningful life. This holistic impact on well-being is a core part of our mission, which you can learn more about on our about us page.

Cognitive defusion is the workhorse skill of ACT for managing anxiety. Where traditional approaches might try to silence the anxious mind, defusion teaches us to change how we listen to it. The goal is to see thoughts for what they are—transient mental events, bits of language—rather than what they proclaim to be—truths, commands, or threats that must be obeyed or eradicated. This section moves from theory to practice, offering concrete, evidence-based techniques you can use to create space from the chatter of worry.

Defusion techniques work by altering the context in which a thought occurs. When we repeat a scary word out loud dozens of times until it becomes just a sound, or when we sing a self-critical thought to a nursery rhyme tune, we are breaking the automatic link between the word/symbol and its feared meaning. We are experiencing the thought directly as a sensory event, not getting lost in its semantic content. This reduces the thought's "stickiness" and believability.

Start with these simple exercises to build the defusion "muscle."

For thoughts with a strong emotional charge, more creative techniques can be powerful.

Let's walk through a real-time application. You're about to walk into a social gathering and feel a surge of anxiety accompanied by the thought: "They're all going to judge me. I have nothing interesting to say."

It's crucial to understand that defusion is not positive thinking, thought-stopping, or dismissal. You are not replacing "I'll fail" with "I'll succeed!" Nor are you trying to blank your mind. You are acknowledging the thought's presence while changing its function—from a director of your behavior to background noise you can act in spite of.

With consistent practice, defusion becomes a swift, automatic response to unhelpful cognitive hooks. It creates the psychological space where choice becomes possible. In that space, you are no longer a prisoner of your thoughts, but a person who can observe them and still choose to move toward what matters. For real-world examples of how individuals learn to navigate these internal challenges, our testimonials page shares stories of personal growth and resilience.

In the storm of anxiety, values act as an internal compass. While anxious thoughts shout "Danger!" and pull us toward avoidance, values whisper "This matters..." and pull us toward vitality. Values clarification is the process of discovering what is truly, deeply important to you as a conscious human being. In ACT, values are not feelings, goals, morals imposed by others, or rigid rules. They are freely chosen, verb-based qualities of action that give direction and meaning to your life.

Anxiety often thrives in a values vacuum or in conflicts between our actions and our values. We might avoid social events (action) while deeply valuing connection (value), creating a dissonance that fuels more anxiety and self-criticism. Clarifying your values provides a powerful alternative motivator that can compete with, and ultimately override, the motive to avoid discomfort.

These exercises are designed to bypass the "shoulds" and tap into authentic desire.

Once you have a list of value words, refine them into directional statements.

Values are the "why" that makes hard "whats" possible. When facing an anxiety-provoking situation, connect it to a value.

Connecting to a value doesn't eliminate anxiety, but it changes its context. Anxiety is no longer a stop sign; it becomes a challenging emotional experience you can carry with you as you walk down a meaningful path. The pull of the value begins to outweigh the push of the fear.

By regularly clarifying your values and consciously linking them to daily actions, you build a life of integrity and purpose. This life, lived in alignment with what you hold dear, becomes inherently more resilient to the inevitable storms of worry and doubt. Your values become the anchor that holds you steady. Discovering and committing to these core directions is a journey, and for more guidance on building a lifestyle that supports it, you can find additional resources on our blog.

Mindfulness is the engine that powers many of ACT's core processes. While often associated with meditation, within the ACT framework, mindfulness is defined behaviorally as the flexible, fluid, and voluntary control of attention to the present moment, coupled with an attitude of openness, curiosity, and acceptance. It is the foundational skill that makes defusion, acceptance, and self-as-context possible. For the anxious mind, which is perpetually time-traveling to catastrophic futures or regrettable pasts, learning to anchor in the present is a revolutionary act of healing.

Anxiety is almost always about a future that has not yet happened. Worry is the cognitive attempt to solve this uncertain future problem. Mindfulness directly counteracts this by:

You don't need to meditate for hours to benefit. Short, consistent practices integrated into your day are most effective.

As mindfulness deepens, it naturally fosters a connection with self-as-context—the observing self. You begin to notice that there is a "you" that is aware of the breath, aware of the thoughts, aware of the anxiety. This "you" is constant and unchanging, while the experiences it observes are in constant flux. This realization is incredibly liberating for someone with anxiety. You are not your anxiety; you are the conscious being experiencing anxiety. This perspective provides a stable ground from which to practice all the other skills.

Modern wellness technology, like advanced smart rings, can serve as an aid to mindfulness practice. These devices can provide objective feedback on physiological signs of stress (elevated heart rate, low heart rate variability) throughout the day. This biofeedback can act as a "mindfulness bell," prompting you to pause and check in with your present-moment experience when your body is showing signs of agitation you may have been ignoring mentally. You can use the data not to fuel worry ("My HRV is low, I'm breaking down!"), but with curiosity and acceptance ("My body is showing signs of stress. Let me pause and take three mindful breaths."). This represents a powerful fusion of external data and internal awareness, a topic we explore further in our resources on how technology can support holistic wellness.

By cultivating mindfulness, you are not creating a peaceful bubble to escape to. You are developing the flexibility to be fully present with life as it is—with all its beauty, boredom, joy, and, yes, anxiety. This capacity to be present, open, and active is the essence of psychological flexibility and the heart of the ACT path to freedom.

The journey through anxiety is often marked by a fierce and exhausting resistance to what we feel. We treat anxiety as an invader to be expelled, a flaw to be fixed, or a fire to be extinguished. The ACT path asks us to consider a radical alternative: what if we stopped fighting the feeling and simply made room for it? This shift from resistance to willingness is the essence of developing an acceptance mindset. It is not a passive surrender but an active, courageous choice to stop struggling with reality as it is, so we can direct our energy toward living.

Resistance is our instinctive reaction to discomfort. It manifests as:

While natural, this resistance creates what Steven Hayes calls "dirty discomfort"—the original pain of anxiety plus the secondary suffering of our struggle against it. It's like being stuck in quicksand; the more we thrash and fight, the deeper we sink. Acceptance is the counterintuitive move of relaxing into the quicksand, which can often reduce its grip.

A common misconception is that acceptance means liking or wanting anxiety. It does not. It also doesn't mean you have to feel willing. Willingness is a behavior—an action of opening up and making space. It is the choice to allow the feeling to be present, without engaging in the internal war to defeat it. You can feel terrified and still be willing to feel terror. This distinction separates you from the emotion; you are not a terrified person, but a person experiencing terror who is choosing to allow that experience.

Developing acceptance is a skill built through practice.

The ultimate test and purpose of acceptance is in the service of your values. Willingness is the key that unlocks committed action.

In this framework, anxiety is no longer the boss that vetoes your plans. It becomes a passenger in the car—perhaps a noisy, fearful one—while you, connected to your values, remain the driver. You learn to say, "I see you're scared, but we're heading in this direction anyway."

The acceptance mindset transforms your relationship with your inner world. Life becomes less about creating a perfect, anxiety-free internal state and more about living a full, meaningful external life, with all your human emotions in tow. This is the foundation for the final, most active phase of ACT: building a life through committed action. To see how others have navigated this shift from struggle to purposeful action, you can read real stories of personal journeys on our testimonials page.

If values are your chosen direction on the map of life, then committed action is the process of walking, step by step, in that direction. It is the tangible, behavioral expression of psychological flexibility. In ACT, taking action is not something you do after you feel better; it is the very process through which you build a better life, while feeling whatever you feel. This turns the traditional model on its head: you don't wait for anxiety to subside to live; you live, and through living, you change your relationship with anxiety.

Committed action is always values-based. It answers the question: "What can I do, right here and now, no matter how small, that moves me toward what matters?" This linkage is crucial because it provides a motivation more sustainable and vital than fleeting feelings of confidence or the absence of fear. You act not because you feel like it, but because it matters.

Taking committed action is not a linear, upward trajectory. It is a cycle of setting goals, acting, encountering barriers, and using mindfulness skills to persist. The process looks like this:

To build momentum, actions should be:

Much of committed action for anxiety involves a form of naturalistic exposure—consciously moving toward previously avoided situations, thoughts, and feelings. In ACT, exposure is framed not as a grim exercise in fear tolerance, but as a vital act of value-living. You're not just entering a crowded room to "get over" your fear; you're entering to connect with people because you value community. This reframe makes the difficult action meaningful and empowering rather than purely aversive.

Setbacks, avoidance, and getting hooked by old thoughts are not failures; they are data and part of the learning process. The flexible, non-judgmental stance of ACT allows you to acknowledge a setback with curiosity: "I avoided that. I was fused with the thought that I couldn't handle it. What's a tiny step I can take now to get back on track?" This compassionate responsiveness builds resilience far more effectively than self-criticism.

Through committed action, you build not just a track record of achievements, but a life of integrity—a life where your actions increasingly match your deepest aspirations. Each step, no matter how small, taken with willingness and awareness, strengthens your identity as someone who can move with anxiety, not just away from it. This process of building a life of purpose is at the core of our philosophy, which you can explore further in our company story.

The principles of ACT are universal, but their application shines when brought to bear on the specific, grinding challenges of anxiety disorders. By targeting the core processes of fusion and avoidance, ACT provides a transdiagnostic framework that can be tailored to everything from Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) to social anxiety, panic, and health anxiety. Let's explore how ACT's six core processes intervene in these specific patterns.

GAD is characterized by pervasive, uncontrollable worry about multiple topics. The ACT view sees worry not as the problem itself, but as a strategy for experiential avoidance—an attempt to mentally problem-solve and thus avoid the feeling of uncertainty or the feared outcomes.

Social anxiety is fueled by fusion with self-critical thoughts ("I'm boring," "They'll judge me") and avoidance of social situations to escape the distress of perceived evaluation.

Panic involves catastrophic fusion with bodily sensations (e.g., racing heart = heart attack) and avoidance of places or activities associated with panic.

This involves fusion with threat-related thoughts about health ("This headache is a brain tumor") and compulsive checking/avoidance behaviors (searching symptoms online, seeking excessive reassurance from doctors).

In each case, the ACT protocol is not about eliminating the specific anxious content, but about changing the functional relationship the person has with that content. The thought "I'll be judged" may still occur for someone with social anxiety, but through ACT, it transforms from a command that dictates isolation to a background noise that can be acknowledged while the person moves toward meaningful connection. This functional approach is what makes ACT so broadly applicable and effective.

The true power of ACT is realized not just in the therapist's office, but when its principles become a woven part of your daily existence—a lens through which you view challenges and a toolkit you instinctively reach for. Developing this integrated practice fosters lasting resilience, turning psychological flexibility from a concept into a lived reality. This final section provides a roadmap for weaving ACT into the fabric of your everyday life.

Consistency in small doses beats occasional intensity. Design a sustainable practice.

Everyday irritations and stresses are perfect opportunities to practice.

The ultimate aim is for these responses to become more automatic—for you to develop what Steven Hayes calls "flexibility reflexes." Instead of the old, rigid reflex of FUSION → AVOIDANCE, you cultivate a new, flexible reflex: NOTICE HOOKING → NAME IT (defuse/accept) → CONNECT WITH PRESENT MOMENT & VALUES → CHOOSE VALUED ACTION.

This is resilience: not bouncing back to a previous state, but bouncing forward with greater wisdom and capacity. It is the ability to withstand life's inevitable storms not because you've built a higher wall, but because you've learned to dance in the rain. Your identity shifts from "someone who needs to manage anxiety" to "someone who is living a meaningful life, who sometimes experiences anxiety."

By integrating ACT into daily life, you move from being a patient or a student of these principles to being an active architect of a vital life. The work is ongoing, but the direction is clear: toward openness, awareness, and engagement with what truly matters. This journey of building a resilient, values-driven life is what we are passionate about supporting, and you can discover more about our approach and resources on our homepage.

We often think of psychological approaches like ACT as existing solely in the realm of thoughts and behaviors. Yet, decades of neuroscientific research reveal a profound truth: our mental practices directly shape the physical structure and function of our brains. This concept, known as neuroplasticity, provides a biological foundation for ACT's effectiveness. When you practice acceptance, defusion, and mindfulness, you are not just learning skills—you are engaging in a form of brain training that rewires the maladaptive neural pathways that sustain anxiety.

Brain imaging studies show characteristic patterns in anxiety disorders. Two networks are particularly relevant:

The problem is reinforced by the link between these systems. A worrying thought (DMN activity) can trigger the amygdala, whose distress signal then fuels more worrying thoughts, creating a vicious, self-amplifying cycle. Experiential avoidance is the behavioral output of this dysregulated brain state.

ACT practices target these exact neural circuits, fostering integration and regulation.

This is where modern wellness technology, like the Oxyzen smart ring, creates a powerful synergy with ACT principles. Such a device provides objective, physiological feedback on your nervous system state—tracking heart rate variability (HRV), resting heart rate, and sleep patterns.

Neuroscience confirms that ACT is more than a coping strategy; it is a transformative discipline for the brain. By practicing its principles, you are gradually sculpting a brain that is less reactive to internal threats, more capable of focused attention, and better integrated in its functioning. This biological shift underpins the lasting change that allows individuals to build a life not defined by their anxiety.

For many, anxiety is amplified by a harsh "inner critic"—a persistent voice of judgment, doubt, and self-denigration. This critic often speaks from deep-seated core beliefs—fundamental, often unspoken conclusions about ourselves, others, and the world ("I am unlovable," "The world is dangerous," "I am inadequate"). Traditional therapy might try to directly challenge and replace these beliefs. ACT takes a different, more oblique and often more effective approach: it seeks not to change the content of these stories, but to change our relationship to them.

From an ACT perspective, the inner critic is not an enemy to be destroyed. It is a part of your verbal mind that developed as a (flawed) protection strategy. Perhaps it learned early on that harsh self-criticism could motivate you to avoid failure or preempt external criticism. The problem is, this strategy is toxic and operates on outdated rules. The critic fuses you to a painful self-concept and drives avoidant behavior.

Trying to argue with the critic ("I am too good enough!") usually fails because you're engaging with its content on its own terms, which only tightens fusion. ACT uses creative defusion to break the literal believability of the critic's pronouncements.

Core beliefs feel like bedrock truths because we've been fused with them for so long. The ACT approach is not to dig them up and replace the bedrock, but to build a new, flexible structure on top of it.

This is where the concept of Self-as-Context becomes profoundly healing. The inner critic and core beliefs are the content of your experience. Self-as-Context is the conscious, observing space in which that content appears. You are not the "failure" story; you are the awareness noticing that story playing out.

Connecting with this transcendent sense of self provides a stable ground. You can look at the critic and the old beliefs from this vantage point and say, "I contain these thoughts and feelings, but I am not defined by them. They are chapters in my book, but I am the book itself—the conscious space holding all the chapters." This perspective is inherently compassionate and liberating.

The most powerful way to undermine a core belief is through embodied, valued action that contradicts it.

Each time you act in alignment with a value while the critic screams, you are teaching your nervous system a new truth: "My actions define me, not my thoughts." You build self-trust based on behavior, not on achieving a perfect, critic-free mental state.

By applying ACT to the inner critic and core beliefs, you move from being at war with these parts of yourself to developing a more mindful, compassionate, and flexible relationship with them. They may never fully disappear, but they can transform from tyrants that rule your life into occasionally grumpy advisors whose input you can notice, acknowledge, and then choose whether or not to follow.

As you become adept at basic defusion, you'll encounter thoughts and mental states that seem particularly tenacious. These "sticky" thoughts—often tied to shame, trauma, or deep fear—and states of emotional overwhelm can feel like they bypass your usual skills. This is where advanced defusion strategies come into play. They are designed for high-intensity internal experiences, helping you to create psychological distance even when the mind is screaming.

When a thought carries a heavy emotional charge ("I'm a fraud," "I deserve this pain"), simple labeling may not feel like enough.

When anxiety or sadness feels all-consuming, it's a state of fusion with a whole swarm of thoughts and sensations. The goal here is not to defuse from each individual thought, but to create space from the entire overwhelming "cloud."

The anxious mind loves to analyze why we feel a certain way, searching for causes in a futile attempt to gain control. This "reason-giving" is often a form of fusion and avoidance.

The key with advanced strategies is to have a personal "menu" of options. Different techniques work for different people and different types of sticky thoughts. The act of choosing a technique is itself an act of defusion—it means you've noticed you're hooked and are taking conscious, flexible action. It proves you are not the thought; you are the person strategically responding to it.

Practicing these advanced techniques when you're not in crisis builds neural pathways so they become more accessible when you are. They empower you to stand in the hurricane of your own mind with a newfound sense of stability and choice, knowing that no thought, no matter how loud or painful, has the final say over your actions. For more structured guidance on navigating these intense mental states, you can find additional resources and coping strategies in our blog.

Anxiety doesn't exist in a vacuum; it profoundly impacts our relationships. It can make us needy, distant, defensive, or conflict-avoidant. Conversely, relationship conflicts are a major trigger for anxiety. ACT provides a powerful framework not just for individual wellbeing, but for cultivating psychologically flexible, deep, and resilient connections with others. It shifts the focus from trying to control your partner or avoid relational pain, to showing up openly and authentically for the connection you value.

Our standard relational patterns are often governed by the same processes that cause individual suffering:

A psychologically flexible approach to repair is transformative. Instead of a defensive, fused apology ("I'm sorry you felt that way"), a flexible repair involves:

By bringing ACT into your relationships, you stop trying to build a conflict-free relationship and start building a conflict-resilient one—a connection that can hold differences, pain, and imperfection because it is anchored in shared purpose, mindful presence, and the courage to show up authentically. This journey of building deeper connections is part of a holistic approach to wellness, which we discuss in the context of our broader mission and community on our about us page.

The modern workplace is a prime breeding ground for the very processes ACT targets: fusion with high-stakes thoughts ("If I fail, I'm ruined"), experiential avoidance (procrastination, perfectionism, conflict aversion), and disconnection from personal values in service of external metrics. Applying ACT principles at work doesn't just reduce stress; it can transform your career from a source of anxiety into a domain of purposeful engagement and vitality.

Common struggles like burnout, chronic stress, and disengagement are often manifestations of:

1. Defusion from Work Thoughts:

2. Acceptance of Workplace Realities:

3. Connecting Work to Personal Values:

This is the most powerful antidote to burnout. Reframe your work not just as a set of tasks, but as an arena to express what matters to you.

4. Committed Action Amidst Workplace Stress:

Leaders can use ACT principles to foster healthier, more innovative teams.

By applying ACT at work, you reclaim your mental space and your sense of agency. Your job becomes less of a stressor you passively endure and more of a chosen domain for meaningful action. You learn to carry stress differently—not as a crushing weight, but as a challenging energy you can channel into valued work. This approach to sustainable, engaged performance is central to our vision for integrating wellness into every aspect of life, a vision detailed in our company's founding story.

Your Trusted Sleep Advocate (Sleep Foundation — https://www.sleepfoundation.org/)

Discover a digital archive of scholarly articles (NIH — https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

39 million citations for biomedical literature (PubMed — https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)

experts at Harvard Health Publishing covering a variety of health topics — https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/)

Every life deserves world class care (Cleveland Clinic -

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health)

Wearable technology and the future of predictive health monitoring. (MIT Technology Review — https://www.technologyreview.com/)

Dedicated to the well-being of all people and guided by science (World Health Organization — https://www.who.int/news-room/)

Psychological science and knowledge to benefit society and improve lives. (APA — https://www.apa.org/monitor/)

Cutting-edge insights on human longevity and peak performance

(Lifespan Research — https://www.lifespan.io/)

Global authority on exercise physiology, sports performance, and human recovery

(American College of Sports Medicine — https://www.acsm.org/)

Neuroscience-driven guidance for better focus, sleep, and mental clarity

(Stanford Human Performance Lab — https://humanperformance.stanford.edu/)

Evidence-based psychology and mind–body wellness resources

(Mayo Clinic — https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/)

Data-backed research on emotional wellbeing, stress biology, and resilience

(American Institute of Stress — https://www.stress.org/)