Anxiety Reduction for Trauma Survivors: PTSD-Informed Approaches

Anxiety reduction approaches informed by understanding trauma and PTSD.

Anxiety reduction approaches informed by understanding trauma and PTSD.

The human nervous system is a masterpiece of evolution, brilliantly designed to detect threat, mount a defense, and return to safety. For trauma survivors, particularly those living with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), this elegant system can feel like a broken alarm, blaring in the middle of a calm day, triggered by echoes of a past that refuses to stay silent. The anxiety that follows is not a character flaw or simple worry; it is a physiological and psychological sequela of survival, a deeply etched pattern in the brain and body.

This pervasive anxiety can color every aspect of life—from disrupted sleep and hypervigilance in crowds to emotional numbness and a paralyzing fear of memories. Traditional advice to "just relax" or "think positive" doesn't just fall short; it can feel insulting to a system operating from a primal playbook. Healing requires a different map, one that honors the intelligence of the survival response while gently teaching the nervous system a new, more flexible language of safety.

This guide is that map. We will delve into the neurobiology of trauma-based anxiety, moving beyond theory into practical, PTSD-informed strategies designed to regulate the nervous system, process stored survival energy, and rebuild a sense of agency. This journey is about empowerment, not eradication. It’s about learning to be the compassionate operator of your own inner alarm system, turning down the volume when needed, and finally finding a sustainable peace. For those interested in how biometric technology can support this journey by providing objective data on your nervous system states, you can learn more about smart ring technology and its applications in trauma recovery.

To effectively soothe trauma-based anxiety, we must first understand its origin. PTSD is not a mental illness in the abstract sense; it is a injury of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and a disruption of the body’s innate threat-processing mechanisms. During a traumatic event, the brain’s survival centers—the amygdala (the alarm), the hippocampus (the memory organizer), and the prefrontal cortex (the logical commander)—are flooded with stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline.

When the event is overwhelming and escape or fight is not possible, the system often defaults to freeze or collapse, a biological imperative seen across the animal kingdom. The problem arises when the immense energy mobilized for survival does not get discharged. As renowned trauma expert Dr. Peter Levine explains, “Trauma is not in the event itself; it is in the nervous system’s response to the event, and the residual impact of that incomplete process.”

This "incomplete process" leaves the ANS stuck in a dysregulated loop. It can vacillate between:

For survivors, daily life can be a exhausting pendulum swing between these states. A smell, a tone of voice, a specific time of day, or an internal sensation can become a trigger—a neurological shortcut that catapults the system back into the past as if the threat is happening now. This is not a conscious choice; it’s a misfire of a brain trying desperately to protect you based on its outdated data.

Recognizing anxiety as a physiological state, not just a psychological one, is the first revolutionary step toward healing. It moves the question from “What’s wrong with me?” to “What is my nervous system trying to tell me, and how can I help it update its software?” This foundational understanding informs every PTSD-informed approach we will discuss. For deeper exploration of the mind-body connection in healing, our resource library offers related articles on nervous system regulation.

Before directly addressing traumatic memories or intense anxiety, establishing safety is the non-negotiable first phase of trauma recovery, as outlined in Judith Herman’s seminal tri-phasic model. Without a felt sense of safety, any therapeutic technique risks re-traumatization. This safety is both external and internal.

External Safety involves creating an environment where your basic needs for security are met. This might mean:

Internal Safety is the cornerstone. This is the ability to feel safe inside your own body, which for many survivors is the very source of danger. Building internal safety is a slow, gentle practice of befriending your bodily sensations.

Establishing this dual sanctuary creates the stable ground from which all other healing work can grow. It’s the container that holds the process. Understanding this mission is core to why companies like ours exist; you can read about our founding story and vision to see how a commitment to genuine safety and empowerment guides product development.

Talk therapy alone often fails to resolve trauma because the experience is not stored as a coherent narrative in the verbal, logical brain. It is stored as fragmented sensory information—images, sounds, smells, and, most crucially, physical sensations and impulses—in the deeper, non-verbal brain and body. Somatic (body-based) therapies address this directly.

These approaches operate on a key principle: the body’s story needs to be completed. The clenched jaw, the tight stomach, the shallow breath are not just symptoms; they are the physiological record of the trauma and hold the key to its release.

Key Somatic Practices for Anxiety Regulation:

Integrating these practices requires patience and often guidance. For survivors curious about how objective biometric feedback can enhance body awareness, exploring how Oxyzen works to track physiological markers like heart rate variability can be a valuable adjunct to somatic therapy.

Breathing is the only autonomic function we can also control voluntarily, making it a direct pathway to influence the ANS. For trauma survivors, breath is often shallow, held, or located high in the chest—a reflection of a perpetual low-grade alarm state. Conscious breathing can be a powerful tool to shift state, but it must be applied carefully. Forceful, intense breathing (like some capsaicin breathwork) can be triggering, as it mimics hyperventilation and can unleash trapped arousal.

The goal in PTSD-informed breathwork is not intensity, but regulation and rhythm.

Developing a personal breath toolkit allows you to intervene in real-time when anxiety begins to spiral. It’s a portable, always-available source of agency.

While trauma is stored in the body, the mind constructs powerful beliefs and narratives to make sense of the incomprehensible. These cognitions often become global, negative, and self-blaming: “The world is completely dangerous,” “I am permanently broken,” “It was all my fault,” “I can never trust anyone.” These thoughts fuel the anxiety cycle.

PTSD-informed cognitive work is not about positive thinking. It’s about accuracy and flexibility.

These cognitive tools help create a “pause” between trigger and reaction, creating space to choose a different response. They are most effective when paired with the somatic and breathwork practices that calm the underlying physiological storm. For practical examples of how individuals integrate these strategies into daily life, our collection of real user experiences and reviews often highlights these cognitive shifts.

For the traumatized nervous system, sleep is not a luxury; it is critical medicine. Yet, sleep is often severely disrupted in PTSD by nightmares, insomnia, hypervigilance, and fear of the vulnerability that sleep brings. This creates a vicious cycle: anxiety ruins sleep, and sleep deprivation lowers the threshold for anxiety and emotional dysregulation, making triggers more potent.

PTSD-informed sleep hygiene goes far beyond standard advice.

Prioritizing sleep restoration is a foundational act of healing. It provides the biological substrate—the repaired neural pathways and balanced hormones—necessary for all other therapeutic work to take hold. Many individuals find that tracking sleep architecture (deep sleep, REM) provides invaluable insight; our FAQ section details how modern wearables can aid in this understanding.

The body under chronic traumatic stress operates in a catabolic state—breaking itself down. Stress hormones like cortisol demand constant fuel, often leading to cravings for high-sugar, high-fat foods, which can further inflame an already inflamed system. Nutritional psychiatry emphasizes that food is not just calories; it is information that directly affects neuroinflammation, neurotransmitter production, and gut health (the “second brain”).

This is not about a perfect diet, but about strategic nourishment. Think of food as one more tool to provide a stable biochemical foundation for your nervous system to heal upon. For a more comprehensive look at biohacking wellness through lifestyle, you can explore our blog for more science-backed tips.

Mindfulness—non-judgmental present-moment awareness—has strong evidence for reducing PTSD symptoms. However, for survivors, closing the eyes and focusing inward can sometimes feel like being thrown into the lion’s den of traumatic memory and sensation. Therefore, trauma-informed mindfulness requires significant modification.

The principle is Choice and Agency. The practice must always feel like something you are doing, not something that is being done to you.

Mindfulness, when adapted, becomes a practice of learning to be present with what is bearable in this moment, and kindly turning away from what is not. It trains the prefrontal cortex to become an observant, compassionate witness to internal experience, rather than being hijacked by it. This mission of empowering individuals with knowledge and tools aligns with the core values you can discover in our company's mission.

Trauma inherently involves a rupture in safe connection—with others, with the world, and with oneself. Isolation then becomes both a symptom and a perpetuating factor of PTSD. Healing, therefore, must involve the careful, deliberate repair of connection. We are neurobiologically wired to co-regulate—to use the calm, present nervous system of another to help soothe our own.

Building this support system requires discernment.

Remember, the goal is not to have a vast network, but to have one or two truly safe, attuned connections. A single secure relationship can be a lifeline that begins to rewrite the internal working model from “people are dangerous” to “some people can be safe, and I am worthy of that safety.” The journey of building this kind of supportive community is something we deeply value, as reflected in the authentic stories shared by our community.

Moving beyond foundational regulation skills, deeper healing often involves directly addressing the disorganized memory networks and fractured sense of self that trauma leaves behind. This phase is not about "getting rid" of the past, but about transforming its relationship to your present life. It involves integrating the fragmented pieces of the experience—and the parts of yourself that formed to survive it—into a cohesive, compassionate whole.

This work is profound and is best undertaken with the steady guidance of a skilled therapist. However, understanding the landscape of these advanced, evidence-based modalities can empower you to seek the right support and demystify the process. The goal is to allow the traumatic memory to finally become what it should be: a story from the past that you own, rather than a present-tense reality that owns you.

When the foundational work of safety and stabilization has taken root, specific therapies can facilitate the neurological "repackaging" of traumatic memories. These approaches work at the level where trauma is stored, promoting integration between the brain's emotion, memory, and reasoning centers.

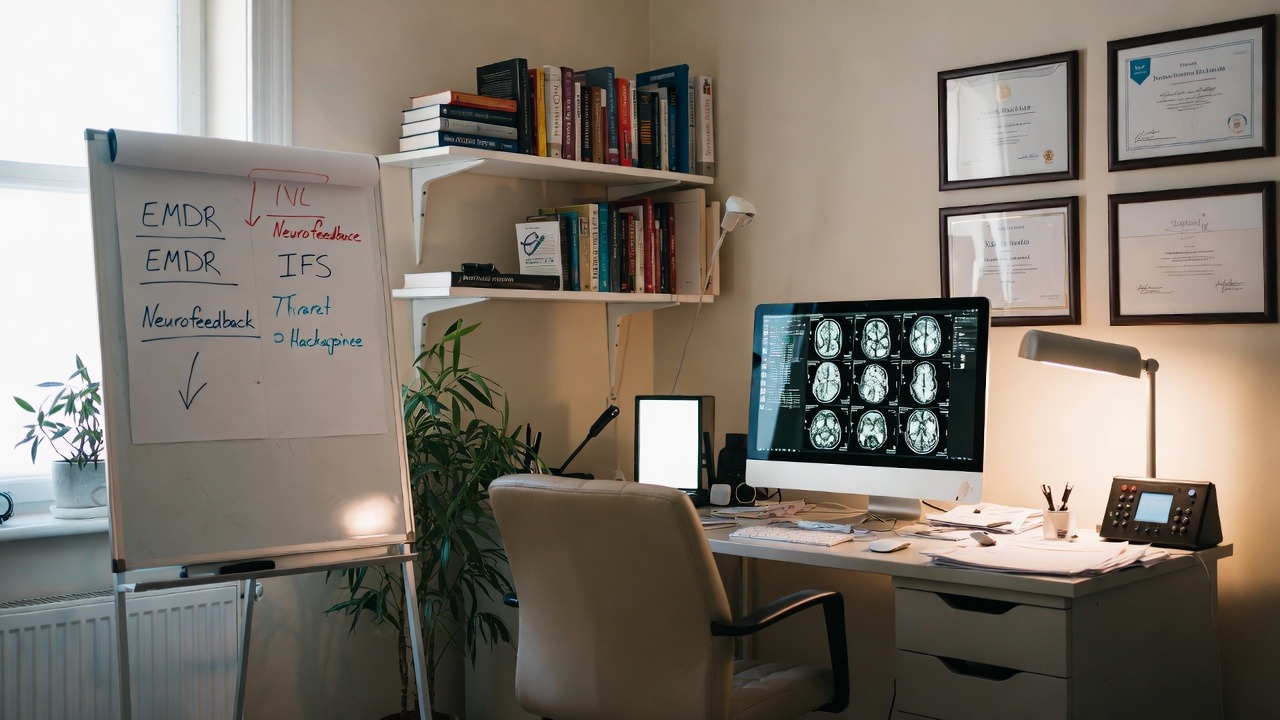

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is one of the most rigorously researched treatments for PTSD. It operates on the Adaptive Information Processing (AIP) model, which posits that trauma symptoms arise when memories are improperly stored in their raw, distressing form. EMDR uses bilateral stimulation (most commonly guided eye movements, but also taps or tones) while the client holds the traumatic memory in mind. This stimulation is thought to mimic the brain's natural processing that occurs during REM sleep, facilitating the movement of the memory from the emotional amygdala to the contextual hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. The memory isn't erased; it's desensitized (loses its emotional charge) and reprocessed (becomes integrated into the narrative of your life). A typical EMDR session will move from the distress of the memory to the installation of a positive belief ("I am safe now" or "I survived, and I am strong"), fundamentally updating the brain's association to the event.

Internal Family Systems (IFS) is a powerful model that views the mind as naturally multiple, composed of various "parts," each with valuable roles and emotions. In trauma, certain exiled parts—carrying the pain, fear, and shame of the event—are locked away. Protector parts, like managers (controlling, perfectionistic) and firefighters (impulsive, numbing), work tirelessly to keep those exiles suppressed, often at great cost to our daily functioning. IFS therapy involves compassionately connecting with these protectors, earning their trust, and then gently unburdening the exiled parts. The goal is to access the core Self—the calm, curious, compassionate, and confident center of every person, which is never damaged by trauma. From this Self-energy, true healing and integration occur. For many survivors, IFS provides a compassionate language for their inner turmoil, transforming self-criticism into curious dialogue. This journey of internal understanding aligns with the personalized insights many seek through modern wellness tools; you can discover how Oxyzen works to provide data that reflects your internal states.

Neurofeedback is a form of biofeedback that trains brainwave patterns. Trauma often leaves a signature in the brain: excessive fast-wave (beta) activity associated with hyperarousal and anxiety, or excessive slow-wave (theta) activity linked to dissociation and hypoarousal. Neurofeedback uses EEG sensors to measure brainwave activity in real-time. Through visual or auditory feedback (like a video game that runs only when your brain produces calmer waves), you learn, subconsciously, to regulate your own brain activity. It's a non-invasive way to directly calm an overactive fear circuit (like the amygdala) and strengthen the regulatory capacity of the prefrontal cortex. While it requires a professional for training, the effects can be lasting, as the brain learns new, more flexible patterns of operation. Those interested in the frontier of brain-based healing will find a wealth of evolving research and discussions in our curated blog on wellness technology.

These modalities represent the cutting edge of trauma treatment, addressing the issue not just in talk, but in the very wiring and networks of the brain and self-system. They offer pathways to resolution that were unavailable just decades ago.

For generations, it was believed the adult brain was largely fixed and unchangeable. The discovery of neuroplasticity—the brain's lifelong ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections—revolutionized our understanding of healing. Trauma carves deep, well-worn pathways of fear and reactivity in the brain. Recovery is the conscious, repeated process of carving new pathways of safety, presence, and choice.

This process is encapsulated in the neuroscientific mantra: “Neurons that fire together, wire together.” Every time you react to a neutral cue with a trauma response, you strengthen the fear circuit. Conversely, every time you encounter a trigger and successfully use a grounding technique, a breath, or a thought challenge, you are firing a new circuit—one of awareness and regulation. With enough repetition, this new pathway becomes the default.

Key mechanisms at play include:

This is why the daily, seemingly small practices are so vital. You are not just "coping" in the moment; you are performing neurosurgery on your own brain. Each time you pause and choose a regulated response, you are voting for the brain you want to build. It’s the biological basis for post-traumatic growth—the potential not just to recover, but to develop increased resilience, deeper compassion, and a more meaningful perspective on life that would not have been possible without the struggle. This commitment to empowering personal growth through understanding is central to our company's mission and vision.

A trigger is any sensory input that is unconsciously linked to the past trauma, launching the survival response. An emotional flashback is a particularly insidious type of trigger where you are suddenly overcome by intense emotions from the past (like overwhelming shame, terror, or despair) without a clear memory or narrative. You regress emotionally to the age at which the trauma occurred. This can feel like free-falling into a familiar but terrifying state with no apparent cause.

Managing these experiences requires moving from victimhood to agency. This involves creating a personalized Trigger & Flashback Response Plan.

Phase 1: Identification and Early Warning

Phase 2: The In-the-Moment Protocol

When triggered or in a flashback, follow a pre-written, step-by-step plan. Yours might look like:

Phase 3: Post-Trigger Processing

After the intensity passes, practice kindness. Do not judge yourself for being triggered. Instead, journal with curiosity: "What does this trigger protect? What old wound is it pointing to?" This turns the trigger from an enemy into a messenger, providing valuable information for your therapeutic work. For support in building and troubleshooting such personal protocols, our FAQ and support resources are designed to help users integrate tools into their unique lives.

Trauma doesn't just shatter your sense of safety; it can shatter your sense of self. The person you were before may feel lost, and the person you are during survival may feel fragmented, ashamed, or unrecognizable. A crucial phase of healing is the conscious, creative reconstruction of identity—not by denying the trauma, but by weaving it into a larger, more resilient narrative.

This is the work of moving from "survivor" to "thriver," or simply to a person who has experienced trauma and is defined by much more than that experience.

Rebuilding identity is slow, iterative work. It involves trying on new ways of being, discarding what doesn't fit, and ultimately integrating all parts of your story—the broken and the whole—into a self you can respect and even cherish.

Healing from trauma is not a linear journey with a fixed endpoint. It is the development of a resilient, flexible system that can meet life's inevitable stresses without collapsing into old traumatic patterns. Long-term resilience is built not through grand gestures, but through the daily, sustainable practice of self-regulation and self-care. It's about creating a lifestyle that supports your nervous system.

Resilience is the capacity to bend without breaking, to feel stress and grief without being defined by them. By cultivating this portfolio of practices, you ensure you have the resources to navigate future challenges from a place of grounded strength, not traumatic reactivation.

Healing thrives in a multi-modal approach. Alongside psychotherapy, several adjunctive practices have strong anecdotal and growing research support for regulating the nervous system and processing trauma non-verbally.

Trauma-Informed Yoga (TIY) is distinct from standard yoga classes. It emphasizes choice, interoception, and present-moment experience over achieving poses. Instructors use invitational language ("if you like, you might explore bringing your arm up..."), offer many modifications, and avoid hands-on adjustments. The focus is on feeling the body from within, reclaiming agency over movement, and tolerating sensation in a safe container. Studies show TIY can significantly reduce PTSD symptoms by reducing physiological arousal and improving body awareness and self-compassion.

Acupuncture works within the framework of Traditional Chinese Medicine to restore the flow of "qi" or vital energy, which is seen as becoming blocked or imbalanced by trauma. From a Western perspective, acupuncture stimulates the nervous system, promoting the release of endorphins and neurotransmitters, modulating the stress response, and improving vagal tone. For survivors, it can be a powerful way to access deep relaxation in the body without needing to talk, directly addressing the somatic dysregulation.

Expressive Arts Therapy (using visual art, music, dance, drama, or writing) provides a vital outlet for experiences that are "beyond words." The process of creation, not the final product, is the therapy.

These modalities offer alternative pathways to the brain and body, bypassing the cognitive defenses that talk therapy can sometimes trigger. They are powerful allies in the integrative healing process, helping to bridge the gap between the felt sense and the spoken story.

In the journey of trauma recovery, subjective feelings can often be confusing or unreliable. Biofeedback and modern wellness technology offer an objective, data-driven window into the inner workings of your autonomic nervous system, transforming abstract feelings of "anxiety" or "numbness" into quantifiable metrics. This demystifies the process and empowers agency.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) is the North Star metric for nervous system health. It measures the subtle variations in time between each heartbeat. High HRV indicates a resilient, flexible system that can smoothly transition between stress and recovery. Low HRV is a marker of a stressed, rigid, or depleted system—common in PTSD. By tracking HRV, you can:

Sleep Architecture Tracking goes beyond just duration. Understanding the breakdown of light, deep, and REM sleep is crucial for trauma survivors. Disrupted REM sleep is often linked to nightmares and emotional processing difficulties, while lack of deep sleep hampers physical restoration and memory consolidation. Data can reveal patterns and help tailor sleep hygiene practices more effectively.

Personalized Biofeedback Training takes this a step further. Devices like smart rings or chest straps can provide real-time feedback on your physiological state. A simple app might guide you through a breathing exercise, only progressing as your heart rate lowers and HRV increases, effectively training your nervous system in real-time. This turns regulation into an interactive learning process.

The key principle is informed self-awareness, not obsession. The data is not a report card; it's a compassionate guide. It helps you move from asking "Why do I feel this way?" to observing, "When my HRV dips, I feel more reactive. What practice can I use to bring it back up?" It externalizes the problem and makes the solution tangible. This philosophy of empowerment through knowledge is at the heart of what we do; to learn more about the technology behind this approach, explore how these tools are designed.

A profound challenge in trauma recovery is the experience of a "setback"—a period where old symptoms return with intensity, often after a time of feeling better. This can lead to devastating thoughts: "I'm back to square one. All my work was for nothing. I'm broken forever." It is critical to reframe this experience.

Healing is not linear; it is cyclical, spiral, or fractal. You may revisit old themes, but never from the same place. Think of it as an upward spiral: you circle back to a familiar feeling of anxiety or grief, but you are now armed with more tools, more self-awareness, and a stronger foundation of safety than the last time you were here. The trigger is the same, but your capacity to meet it is transformed.

Understanding the non-linear path prevents discouragement from derailing your journey. Each time you navigate a setback with even a sliver more awareness and compassion than before, you are building profound, unshakeable resilience. For ongoing support and stories from others on this path, our blog is a continual resource.

For many survivors, the trauma was not a single, discrete event but a prolonged, inescapable ordeal, often occurring in childhood within the very relationships and environments meant to provide safety. This is the terrain of Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD). While sharing core symptoms with PTSD, C-PTSD involves a more pervasive fragmentation of the self, characterized by profound disturbances in:

The anxiety here is not just about fear of external triggers; it's an identity-level anxiety—a chronic, sinking dread of being exposed as flawed, a terror of abandonment, and a deep-seated shame that feels like a core truth. The survival strategies—such as fawning (people-pleasing to avoid conflict), extreme dissociation, or chaotic relationship patterns—are often more entrenched and ego-syntonic (feeling like "just who I am").

Healing from C-PTSD requires all the tools for PTSD, applied with even greater patience and nuance, plus additional focus on:

Reparenting the Inner Child: The work here is explicit and central. Because developmental needs for safety, attunement, and validation were not met, the adult self must learn to provide them. This involves:

Healing Relational Trauma: The wound happened in relationship, so healing must involve corrective relational experiences. The therapeutic relationship is paramount. A consistent, boundaried, empathetic therapist provides a living model of a secure attachment, challenging the survivor's deep-seated beliefs that they are "too much" or "not enough" and that others are inevitably untrustworthy or abusive.

Addressing Toxic Shame: Shame in C-PTSD is not about doing something wrong, but about being wrong at the core. Cognitive strategies alone cannot touch this. Healing requires:

The journey with C-PTSD is often longer and involves grieving not just events, but a lost childhood and a stolen sense of self. Yet, the transformation can be equally profound, as survivors build an identity not from the ashes of what was done to them, but from the bedrock of their own rediscovered worth and authenticity. This deep, personal reclamation is the ultimate goal, and understanding its challenges is part of our commitment to comprehensive wellness support.

While internal work is essential, trauma recovery cannot be completed in a vacuum. Isolation is both a symptom and a cause of suffering. Re-engaging with community—in safe, chosen, and often new ways—is a powerful step in reclaiming a sense of belonging and purpose. Furthermore, transitioning from feeling like a passive victim to becoming an active advocate can be a pivotal point of post-traumatic growth.

Finding Your Tribe: This is not about returning to old, potentially triggering social circles, but about intentionally seeking communities that share your values or understand your journey.

The Power of Advocacy: For some, healing finds its most potent expression in helping others. Advocacy transforms pain into purpose. This does not require public speaking or political campaigning (unless that calls to you). Advocacy can be:

Engaging in community and advocacy counteracts the core trauma messages of "You are alone" and "You are powerless." It rewires the brain for connection and agency, proving to yourself that your voice and your experience matter. Seeing how others navigate this reintegration can be inspiring; reading real stories of resilience and reconnection from our community members often highlights this vital phase.

Trauma can freeze time, anchoring you in the past. A sign of healing is the gradual return of the ability to imagine and plan for a future—not a perfect, pain-free future, but one that holds possibility, interest, and choice. This involves reactivating the brain's prefrontal cortex for future-oriented thinking and learning to build relationships on a new foundation.

Setting Trauma-Informed Goals: Traditional "SMART" goals can feel overwhelming and triggering to a nervous system used to failure or threat. Instead, practice setting GENTLE goals:

For example, instead of "Get a new job," a gentle goal might be: "Spend 15 minutes this week updating my LinkedIn profile with self-compassion. If I feel triggered, I will stop and ground myself." This builds success upon micro-success.

Navigating Intimate Relationships: Trauma profoundly impacts intimacy—both emotional and physical. Rebuilding this requires immense communication and patience.

Embracing Lifelong Growth: Healing is not a destination where trauma is erased. It is the ongoing process of building a life rich enough, meaningful enough, and resilient enough to hold your story without being defined by it. It means continuing to learn, adapt, and apply your hard-won wisdom. It involves regular check-ins: "What does my nervous system need today? What dream feels whisper-soft but persistent? What old wound is asking for a little more compassion?" This mindset of continuous, compassionate self-evolution is what we aim to support; for those with technical questions on tools that aid this journey, our FAQ resource is always available.

The path of anxiety reduction for trauma survivors is not a straight line out of suffering. It is a spiral journey inward and upward—a courageous pilgrimage to reclaim the territories of your own body, mind, and spirit that trauma claimed. We began by understanding that anxiety is not a flaw, but a faithful, if misguided, echo of a survival system doing its job. We built from the foundational necessity of safety, learning that before we can change, we must feel secure enough to be present.

We explored the language of the body through somatic practices, discovering that the whispers of sensation hold the key to unlocking frozen survival energy. We harnessed the breath as a direct remote control for a dysregulated nervous system, and we gently challenged the cognitive narratives that kept us imprisoned in the past. We honored the sacred restoration of sleep and nourished our biochemistry to provide a stable scaffold for healing.

We ventured into the deeper waters of memory reprocessing with advanced modalities, armed with the knowledge of our brain's miraculous plasticity. We developed plans to meet triggers and flashbacks not as victims, but as skilled navigators. We undertook the sacred work of rebuilding an identity woven from both fracture and strength. We built a sustainable practice of resilience and embraced integrative arts that speak the soul's language.

For those with complex trauma, we acknowledged the deeper layers of relational wounding and identity shame, affirming that this path requires and deserves exquisite patience. We recognized that healing finds its full expression in community and advocacy, transforming isolation into connection and powerlessness into purpose. Finally, we dared to look toward a future filled with gentle goals and authentic relationships.

This journey, in its entirety, moves you from a state of reactivity—where the past is in the driver's seat—to a state of responsive agency. It’s the difference between being a prisoner of your nervous system and becoming its compassionate steward. The anxiety may not vanish, but its role changes: from a deafening siren controlling your life to a sometimes-sensitive alarm you know how to quiet, understand, and respect.

Thriving after trauma is not about the absence of pain or memory. It is about expansion. It's about your "Window of Tolerance" growing so wide that you can hold intense joy, deep grief, creative passion, and ordinary calm—sometimes all in a single day—without fragmenting. It is about the embodied knowing, deep in your bones, that you are more than what happened to you. You are the one who survived, the one who learned the map, the one who dared to heal. Your story is not over; it is being written with every conscious breath, every act of self-kindness, and every moment you choose presence over the past.

You are not just reducing anxiety. You are reclaiming your birthright to a life of depth, meaning, and peace. For continued support, deeper dives into these topics, and a community walking a similar path, remember that resources like our comprehensive blog on wellness and resilience are here for you. Your journey is unique, but you do not have to walk it alone.

Your Trusted Sleep Advocate (Sleep Foundation — https://www.sleepfoundation.org/)

Discover a digital archive of scholarly articles (NIH — https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

39 million citations for biomedical literature (PubMed — https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)

experts at Harvard Health Publishing covering a variety of health topics — https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/)

Every life deserves world class care (Cleveland Clinic -

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health)

Wearable technology and the future of predictive health monitoring. (MIT Technology Review — https://www.technologyreview.com/)

Dedicated to the well-being of all people and guided by science (World Health Organization — https://www.who.int/news-room/)

Psychological science and knowledge to benefit society and improve lives. (APA — https://www.apa.org/monitor/)

Cutting-edge insights on human longevity and peak performance

(Lifespan Research — https://www.lifespan.io/)

Global authority on exercise physiology, sports performance, and human recovery

(American College of Sports Medicine — https://www.acsm.org/)

Neuroscience-driven guidance for better focus, sleep, and mental clarity

(Stanford Human Performance Lab — https://humanperformance.stanford.edu/)

Evidence-based psychology and mind–body wellness resources

(Mayo Clinic — https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/)

Data-backed research on emotional wellbeing, stress biology, and resilience

(American Institute of Stress — https://www.stress.org/)